During World War II, in colonial Korea, guest speakers from mainland Japan frequently visited to give speeches aimed at boosting morale and reinforcing loyalty to Imperial Japan. These speakers were often staunch Imperialist ideologues whose words were crafted to inspire support for the war effort. Among them was Ryōichi Sasakawa, the founder and leader of the National Essence League (国粋同盟), one of the most extreme right-wing political organizations in wartime Japan. Sasakawa admired Benito Mussolini and modeled his organization on Italian Fascist principles.

Portrait of Sasakawa in August 1943 article.

At the end of World War II, Sasakawa, along with Kishi Nobusuke (Shinzo Abe's grandfather) and Kodama Yoshio, were classified as Class A war criminals and imprisoned at Sugamo Prison after Japan's defeat. However, they were later released by the Allies due to his staunch anti-communism. Sasakawa, Kishi, and Kodama became key players in the political landscape of post-war Japan, continuing their careers as unreformed Imperialists to try to reconstitute as much of the old Imperial Japan as possible in the post-war environment. Among other things, Sasakawa also played a key role in establishing a relationship between the Unification Church of Reverend Moon and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party of post-war Japan (this is probably a topic that deserves its own post).

The article shared here offers a glimpse into Sasakawa's 1943 visit to China and Korea. While he held a position as a Diet parliament member, Sasakawa spent much of the war giving motivational speeches to the Imperial Army and the general public across the Empire to boost war morale. In his remarks during this visit, he encouraged leaders to "punch Koreans with an iron fist" if they seemed unsteady and unfocused (ふらふら), claiming that such actions were acts of love (可愛ければこその鉄拳である) necessary to bring them back in line. This philosophy aligned with the broader Imperial Japanese military culture, which heavily relied on corporal punishment. In this way, the physical abuse of Koreans was normalized in Imperial Japanese culture and rationalized as an act of tough love to mold the Koreans into 'true Japanese people'.

Interestingly, this physically abusive training style found favor with figures like Park Chung-hee, the late South Korean dictator, who was trained as an Imperial Army officer during the war. Park even approvingly referred to such harsh methods as ビンタ教育. In this context, it would seem that, as the dictator, Park played a key role in nurturing the culture of physical abuse that was pervasive in the South Korean military at the time.

In addition to Sasakawa's visit, I have included other articles from the same newspaper page that shed light on the broader context. One details the "training" of Koreans in various dojos across Japan, such as Tokyo and Fujisawa, where they were subjected to similar physical discipline to mold them into 'true Japanese people.' The fact that the colonial regime went through the trouble and expense of relocating them to mainland Japan for training strongly suggests that these dojos were meant to 'train the trainers', so that the graduates would go back to Korea as senior teachers to mold generations of Koreans into 'true Japanese people'. Another describes a propaganda lecture by a less prominent Imperial Army officer who visited Manchuria and Seoul. These lectures were often free to ensure mass attendance.

[Translation]

Gyeongseong Ilbo (Keijo Nippo) August 10, 1943

Relentless Drive Without Reasoning: Diet Member Sasakawa Speaks Cheerfully

"One must become a fanatic for patriotism and love for others, otherwise it is useless. Once you achieve this state, you become impervious to the heat, the cold, and neither praise nor criticism will matter. Farmers can till their fields, and merchants can conduct their trade without distractions." With these words, Diet member and head of the National Essence League, Ryōichi Sasakawa, passionately struck the table with his fan, his eyes flashing brightly. Returning from an inspection tour of Central and Northern China to promote the "Yamamoto Spirit," Sasakawa entered the city on the 6th and spoke on the 9th at the Hantō Hotel, under the blazing afternoon sun.

"I am delighted that Korea has finally introduced a conscription system and that the Navy's special volunteer system will be implemented. This is good news. Once it is fully operational, the theory of Japanese-Korean Unification will no longer be reversible. Government and civilians alike must act as one, with words and actions in perfect alignment. I met with both the Governor-General and the Director-General, and they were already out working by 7 a.m. That is how it must be. Their enthusiasm was evident. Words and actions must be consistent. The people must be inspired to take action. Bureaucrats must not worry about saving face. There is no room for reasoning. Only with this mindset can we achieve increased production, training, and ultimately serve the nation. Overcomplicating things is unnecessary. To win, we must set reasoning aside. If we get bogged down by logic, we will fail to act," Sasakawa said, striking his knee with his fan.

His fan bore the words, "Thunder is the music of the heavens, earthquakes are the dance of the earth, everything is to be enjoyed," written by himself. He continued, "The guidance of our Korean compatriots requires great effort and strength. Even in daily training, forging the spirit is essential. Without a firm and unyielding stance of the spirit, one quickly becomes unsteady and unfocused. In such moments, a leader must 'Bam!' deliver a punch with an iron fist to restore their composure. This is an iron fist born out of love. By casting aside selfishness through this great love and strength, and by leading by example, the people can advance with unwavering resolve, dedicating themselves fully to increased production and rigorous training, moving forward with all their strength toward victory."

Like a Zen monk devoted to self-sacrifice and patriotic sincerity, Sasakawa slightly smiled, his eyes sparkling with determination.

Instilling the "Japanese Spirit"

Misogi Training for Korean Students in Japan

Tokyo Report – In order to fully instill the true "Japanese Spirit" into Korean students preparing to enter the job market in September, the Korean Scholarship Association has been organizing intensive training sessions in Mitaka Town, Tokyo; Ichinomiya Town, Gunma Prefecture; Fujisawa City, Kanagawa Prefecture; Ōta Town and Kashima Town, Ibaraki Prefecture. One such session at the Mitaka Town Prosperous Asia Training Dojo ran from the 7th to the 10th of last month, with thirty-five students participating in a rigorous training retreat. Under the guidance of Takayama Shaji, a priest of the Kugenuma Inari Shrine, and Takeo Amagawa, a kendo instructor from the Central Training Center for overseas compatriots who are originally from Jeollabuk-do, students engaged in four days of Misogi purification rituals, worship for twelve hours, six hours of lectures, three hours of martial arts practice, and nine hours of agricultural work each day.

A typical day's schedule began at 4:30 a.m. with the sound of clappers signaling wake-up, followed by a refreshing Misogi morning purification at Senkawa, surrounded by the greenery of Musashino. The distinct feature of this dojo's program is its emphasis on "purification through labor," or soil purification, promoted by Takayama Shaji, based on the spirit of Japan's ancient farming traditions. This method seeks to instill the true Japanese spirit through hands-on practice while strengthening war power under wartime conditions. It is evident that the training is closely tied to practical life. When asked about their experiences, a participating student remarked,

"Recently, sitting for long periods was quite painful, but as I became accustomed to it, I gradually came to understand the Japanese spirit through discipline. I also realized that Japan and Korea share a deep-rooted family-centered ethos since ancient times. This realization brought me great joy. I now understand that it is our duty to develop Korea’s family-oriented principles into a larger, family-centered framework."

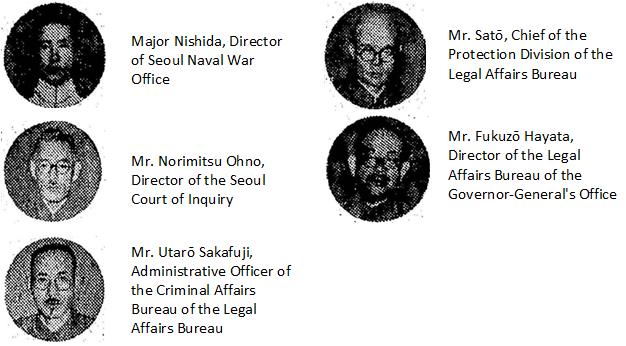

Lecture by Major General Kaneko Teiichi

To Be Held at Seoul Citizens Hall on the 12th

While the Imperial Army continues relentless battles on land and sea against the demonic Anglo-American forces, our publication and the Maeil Sinbo newspaper have arranged for Major General Teiichi Kaneko, a former army officer and current member of the House of Representatives with deep ties to Korea, to participate in the Second Prosperous Asia Group Meeting in Shinkyō, Manchuria, on the 16th. On his return, he will deliver a lecture on the "Current and Final Stages of the World War" on the 22nd at 2 p.m. at Seoul Citizens Hall. Admission to this lecture will be free of charge.

500-Yen Donation Commemorating the Implementation of Conscription

On the 9th, Kawakami Hiroasa, the representative of the Cheondogyo Temple, visited the office of the Korean Federation of National Power to express gratitude for the implementation of conscription and presented a donation of 500 yen collected by members.

[Transcription]

京城日報 1943年8月10日

理窟抜きの驀進だ

笹川代議士朗らかに語る

『愛国愛人狂にならんと駄目。これになれば暑いことも寒いことも判らん。毀誉褒貶耳に入らずに農民は田を耕し商人は商売が出来るんだ』と、愛国の熱情を扇子と共にデンと卓に叩きつけた、国粋同盟総裁代議士笹川良一氏の目がきらりと光った。中支、北支を視察”山本魂”鼓吹行脚の帰途六日入城。宿舎半島ホテルで九日烈日の西陽を受けながら総裁は語るのだ。

『朝鮮も愈々徴兵制が布かれ、海軍特別志願兵制も実施されることになり嬉しい。良いことだ。これが出来上がれば内鮮一体論などはもう過去に翻すことになるのだ。官民一体、言行一致で行かなければならん。僕は総督にも、総監にも会ったが、御両人共に朝七時頃にはもう出掛けていた。これでなければいかんのだ。大いに張り切っとるね。言行一致だ。国民をして感奮興起せしめなければならん。役人は面子を考えてはいかん。理窟抜きだ。この気持ちになってこそ増産も錬成も出来、国家の為に尽くすことが出来るのだ。むずかしいことを言うてはいかん。勝ち抜くためには理窟は抜きだ。理窟を並べていては理窟倒れとなり実行は出来なのだ』と、膝をポンと叩いて総裁は扇子を開いて見せた。

それには『雷鳴りは天の音楽、地震は地球の舞踏、万事楽しむ』と自ら書いてあった。そしてまた『半島同胞の指導は大変と力を必要とする。日々の錬成にしても魂の錬成が必要だ。魂に不動の姿勢がなければすぐふらふらとなる。その時指導者はボカンと一つ鉄拳をくらわせばふらふらは立ち直る。可愛ければこその鉄拳である。この大愛と力でもって私心を去り率先垂範してこそ民衆は理屈抜きに勝ち抜くために増産へ錬成へ命がけで驀進出来るのだ』

滅私奉公、愛国の至誠に徹した禅坊主のような心境である総裁はきりっとしまった口元を微かに綻ばせ眸で笑った。

叩き込む”日本精神”

半島出身学生に禊の錬成

【東京電話】九月就職戦線に進出する半島出身学生に真の日本精神を体得せしむべく朝鮮奨学会では東京都三鷹町、群馬県一ノ宮町、神奈川県藤沢市、茨城県太田町同じく鹿島町などに同会主催の錬成会を開催している。その一つ三鷹町興亜錬成道場は去る七日から十日まで三十五名の学徒が合宿錬成にいそしんでいるが、鵠沼稲荷神社高山社司、全北道出身海外同胞中央錬成所剣道教師天川武雄氏指導の下に四日間を通じて禊、拝神十二時間、講話六時間、武道三時間、農耕九時間の日程である。

一日の日課はまず午前四時半拍子木の音とともに起床、武蔵野の緑に包まれた千川での清々しい暁の禊にはじまる。この道場の一特色は高山社司の主唱の下に我が国古来の農民精神を汲み、特に汗を通じての『禊』たる土の禊を強調している点で、実戦によって真の日本精神を体得させるとともに決戦下戦力増強につながる。真に生活に即した錬成を目指していることが、はっきりと看取される。右錬成参加の学生の体験を訊くと、

「最近は坐ることが非常に苦痛でしたが段々馴れるに従って日本精神が躾けながらわかって来ました。家族を中心とする点に於いて太古以来内鮮は共通したものを持っていることがわかり、こんな嬉しいことはありません。今後は朝鮮に於ける家族主義をより大きな家族中心へと発展させることがわれわれの努力すべき義務であるとわかりました」と語っていた。

金子定一少将の講演会

十二日府民館で

鬼畜米英を向かうに廻して皇軍は陸に海に日夜間断なき攻防戦を繰り返しているとき、本社及び毎日新報社では朝鮮に馴染み深い武人たる現衆議院議員金子定一陸軍少将が来る十六日より新京で開催する第二回興亜団体懇談会に出席し、帰途来城するのを機会に、来る二十二日午後二時より府民館で時局講演会を開催する。金子少将の演題は『世界大戦の現段階と最終段階』と決定。当日は入場無料である。

徴兵記念に五百円献金

九日、朝鮮聯盟事務局に天道教会代表教領川上広朝氏が訪れ、徴兵制実施に感激し会員が集金した五百円を献金。

Source: https://archive.org/details/kjnp-1943-08-10/page/n2/mode/1up